About Aasivissuit: Five Questions for Jasper Coppes

In 2019, Jasper Coppes produced Aasivissuit together with VRIZA’s Lonnie van Brummelen, Uilu Stories’ Aka Hansen, and a crew in Greenland and the Netherlands. The film follows two park rangers at work and on expeditions through the sunlit grasslands of West Greenland. As they talk, they exchange new and old knowledge of the land, for example, how ancient fertile sediment from Greenland is used to fertilize depleted soil abroad, and how microbes have adapted to deal with pollution. In the meantime, the landscape and its inhabitants perform their acts.

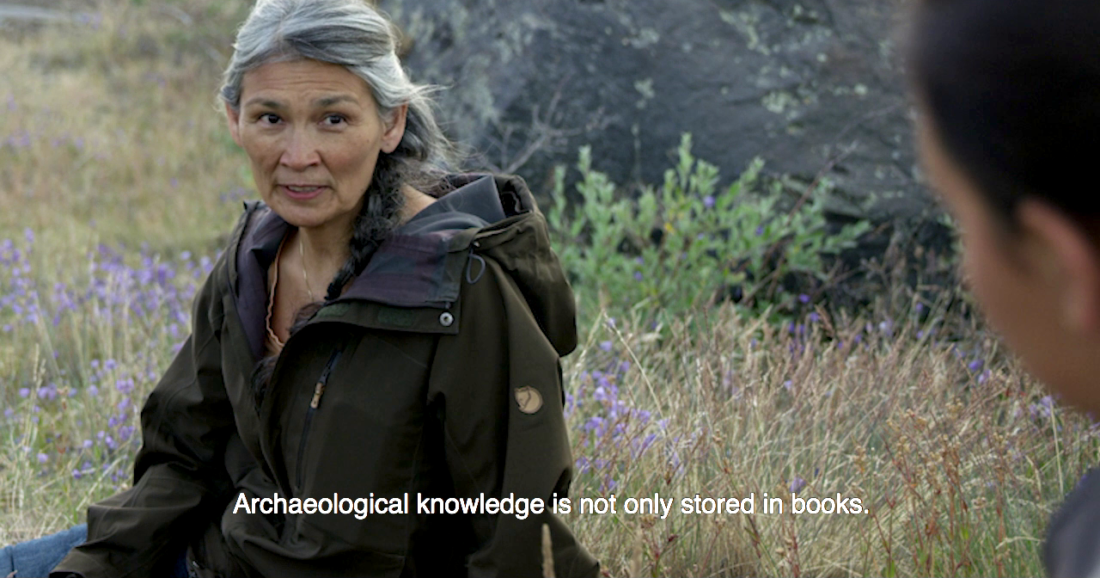

Kerstin Winking: Unlike most documentaries, Aasivissuit has no voice-over. Sometimes the storytelling of your human characters continues while the camera moves away from their faces, deeper into the subject matter they are talking about. Who are the people you worked with for Aasivissuit? What is their specific relationship to this habitat?

Jasper Coppes: Instead of an authoritative voice that sums up knowledge about the landscape, I wanted the landscape to speak for itself. Certainly, the landscape doesn’t need a filmmaker for that, because it constantly speaks for itself through sandstorms, the crushing thunder of a waterfall, the call of the raven, etc. However, in my view, we humans could use some help to become more attuned to a larger conversation led by the environment. I did that by first consulting local people. In 2016 I joined a camp with Angaangaq Angakkorssuaq, a shaman from Greenland, in the Aasivissuit area just north of the Arctic Circle. In 2017 I spoke with Greenlandic artists living in the capital, Nuuk. In August 2018 I organized a gathering with local nature experts to discuss the film project and receive their feedback. These conversations were important guidelines for making the film. The two people you see in the film have an intimate knowledge of the environment of Aasivissuit: Adam Lyberth is a nature guide who told me about how the landscape communicates to him. Francisca Olsen was the first park ranger Greenland ever appointed for the Aasivissuit area.

KW: When I read the descriptions of your earlier film works, the words ‘archeology of the present’ made me curious. What do they mean to you, your practice and to Aasivissuit specifically?

Jasper Coppes: The archeology of the present is a term that came to me during my previous film project, Flow Country, which I developed with Orkney [Scotland] based archeologist Dan Lee. I think of it as what informs my desire to search for traces of the past on the surface, rather than digging and thinking that the past resides somewhere deep down. The past is always also ‘here and now’. This was one of the themes I continued to explore in the film project in Greenland. We shot scenes on analogue film to create the sensation of the past merging with the present, that they exist on the same plane.

Aasivissuit is one part of an area of cultural heritage called ‘Aasivissuit – Nipisat’ that stretches from the sea to the inland ice sheet. UNESCO recently recognized the area’s tangible and intangible cultural heritage as linked to climate, navigation, and medicine. Here, the archeology of the present took on a new shape. In Greenland, archeological artifacts used to be well preserved at the surface of the frozen soil. But now that the temperatures are rising, artifacts such as human remains are rapidly decomposing. At the site where we were filming, you could literally see graves sinking away into the melting permafrost. How the past can continue to pervade the present became clear to me from the conversations I had with the Greenlandic archeologist Pauline Knudsen. She had been interviewing people from the northern tip of Greenland to discover what still remained of the ancient practices of the people who live in this environment. I learned that the archeology of the present is not only about artifacts but also about people’s contemporary habits, gestures, attitudes, and feelings.

KW: A striking characteristic of Aasivissuit are the animal perspectives. At one point, the camera is in a plastic bag with dead fish, and a fly moves in close to your lens. In other scenes, we watch the magnificent landscape from a birds-eye perspective or a microbe crawling under a microscope. What do you aim to achieve with these animal perspectives?

JC: The underlying thread is to show that the landscape, which is the subject of the film, is not only observed, examined, and explored by humans, but that all sorts of creatures have perspectives on it as well. I am invested in getting as close as I can to these other perspectives. I try to make the image inhabit the lifeworld of a microbe, for instance. I want to create the experience of being spoken to by a raven, instead of speaking about it. Besides framing their presence, the camera also registers how these life forms have their own ways of inhabiting and communicating with the world. Although filmmaking is a human construct, I think we can try to use cinema to break away from the positivist idea that our knowledge of the world is dependent on our mental frameworks. We can use it to remember that what we create is merely one part of an endless multitude of perspectives. I believe that cinema has a great potential to open up our senses to these perspectives.

Photograph by Wim van Egmond.

KW: We watch some birds fly through the sky, but we also see fish wrapped in plastic foil and dogs on chains and in cages. What kind of relationship between nature and technology does Aasivissuit depict?

It is tempting to depict the environment in Greenland as a pristine landscape. Huge parts of it have never been seen, because they have been covered by ice for centuries. What we call ‘nature’ in the west, we either exploit, destroy or ignore. In Greenland that’s generally considered an odd way of being in a relationship with the land and its creatures. I wish for the film to reflect that. The dogs are a good example of the frictions in the relationship between humans and animals. Not so long ago, the sled dogs lived together with people in the town. Every owner had their dogs chained next to the house, where their barking and howling was part of the daily soundscape. But today most dogs are kept at the edge of town. In that sense, the film breaks with the stereotype of people in Greenland being framed as living in harmony with nature. In one of the last scenes, the park ranger Francisca talks about microbes that have adapted to toxic environments. These microbes are also found in the fish that people eat. It is a continuous circle of interdependence that is neither harmonious nor hostile.

KW: You recorded Aasivissuit at a time when the Wall Street Journal lifted the lid on Donald Trump’s idea of buying Greenland. How did the people you worked with react to the reports?

JC: The news broke just after we had recorded our last shoot. In Greenland, everyone was making jokes about it. Trump’s strange offer confirmed the narrative we constantly hear about Greenland’s ‘virgin soil’ that is abundant with oil, uranium, gold and diamonds just waiting to be exploited. Of course, it is easy to be critical of this, but in Greenland these resources might help the island become independent from Denmark. There already are a lot of different opinions about this problem. I wanted the film to open up the perspective of the landscape itself: neither a pure resource opportunity nor a pristine wilderness. Its future will depend on the way in which humans and other beings live together. From the various encounters I’ve had with people and ecosystems in Greenland I get the sense that they have a lot of experience navigating this relationship. In the beginning of the film, the two protagonists talk about Greenlandic rock flower, which could potentially become an export product for use in soil restoration elsewhere in the world. I think this is a strong alternative to the dominant exploitation narrative. I am currently following the trace of this sediment for a future project.

Photography by Ulannaq Ingemann, unless otherwise indicated.